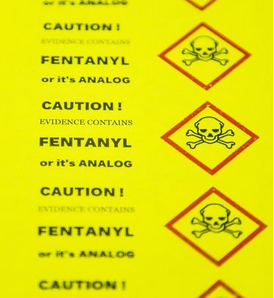

“CAUTION! EVIDENCE CONTAINS FENTANYL or its ANALOG”

September 12, 2017

A half-used sheet of fluorescent-yellow stickers at a workstation in the state’s crime lab is an indicator of more than just the phrase stamped in bold, black letters:

“CAUTION! EVIDENCE CONTAINS FENTANYL or its ANALOG”

It’s proof of an ever-intensifying and dangerous national issue that has spurred calls for action and forced changes, including within the state’s largest law-enforcement agency.

Citing rising concerns about the extra-potent synthetic opioid, the Arizona Department of Public Safety quietly instituted a blanket protocol change that bars troopers from conducting in-the-field testing on suspected drugs. Instead of fumbling with heroin or other illicit substances that might be laced with fentanyl during a traffic stop, troopers now send samples to the DPS laboratory where more rigorous testing can be completed in a controlled environment.

While intended to promote trooper safety, the policy change has also resulted in a backlog of more than 2,000 controlled-substance cases in need of testing. Left unchecked, that delay could hinder prosecutors’ ability to file formal criminal charges, effectively stalling a case before it gets going, officials said.

That backlog in controlled-substance lab testing is so significant, it bucked the steadily declining backlog of all pending DPS tests, including DUI blood screening, fingerprint analysis and sex-assault kit evaluations.

“We don’t have enough staff to do that sort of complete confirmation testing on everything that’s coming in the door,” said Beth Brady, lab manager, during a lab tour this week with The Arizona Republic.

“So we had to come up with another plan.”

National fear, overblown concern?

Widely reported incidents of substances affecting first responders elsewhere in the U.S. have contributed to the DPS policy change.

Perhaps most notably, a police officer in Ohio suffered an accidental overdose this year after coming in contact with fentanyl. He took precautions during a traffic stop earlier in his shift and was back at the station chatting with colleagues when he brushed something off his shirt sleeve.

That something turned out to be opioid residue. Seconds later, his speech slowed and he fell to the floor.

Paramedics gave him a dose of opioid-reducing naloxone, known by its trade name Narcan, and he made a full recovery. His story made national headlines, and the incident has since been cited across the country by law enforcement as first responders grapple with how to handle increasingly common, inherently dangerous opioid encounters.

His wasn’t the only cautionary tale to gain traction recently in law-enforcement circles.

A SWAT team in Connecticut was attempting to bust up a heroin operation in September when a flash-bang grenade tossed into a house sent fentanyl and other opioid residue airborne

Police breathed in some of the substances, and 11 officers were briefly hospitalized.

A team of investigators was conducting field tests in New Jersey last summer when, while closing a package of drugs, a small amount went airborne, reportedly sickening two officers.

There have been no apparent cases in Arizona — yet.

As the better-safe-than-sorry policy shift away from field testing gains traction, some medical professionals maintain it is an unnecessary precaution fanned merely by anecdotal evidence that doesn’t hold up to science.

The risk of “clinically significant exposure” to law enforcement and other first responders remains “extremely low,” according to researchers with the American College of Medical Toxicology, a group that published a July position statement seeking to allay some of the concern.

Researchers highlighted anecdotes — many of those that have been fanned by social and traditional media — of police and firefighters reporting symptoms of incidental overdoses absent any “objective signs of opioid toxicity, such as respiratory depression.”

Andrew Stolbach, an emergency-room doctor at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, co-authored the position statement. In an interview this week with The Republic, he attributed some of the public concern about fentanyl to a slow-to-react medical community hesitant to wade into the issue.

He acknowledged the risks associated with encountering extremely dangerous opioids, like fentanyl, but reiterated that proper, standard precautions can ensure the safety of police and firefighters working with substances in the field.

Field tests were no exception.

“From my standpoint, I think if you take just reasonable precautions … this kind of testing could be safely done,” Stolbach said.

Of equal import, he said, was the potential for delays in patient care due to safety concerns among first responders, whether on the law enforcement or emergency-medical services end of the spectrum.

“Our hope is that first responders feel that they can safely take care of opioid-poisoned patients if they just use basic, reasonable precautions,” Stolbach said. “Our hope is that care for patients isn’t delayed by first responders who are worried about their own safety. Because they are safe.”

Protocol shift, backlog surge

With exposure anecdotes stacking up, agencies across the country this summer have increasingly halted field tests, opting to do what the Arizona DPS did in November.

The logic has been simple enough: Perform tests in a controlled environment with established safety procedures, minimizing the potential for accidental, potentially lethal, exposure to highly potent substances.

Except fentanyl and the like are only a fraction of what troopers and other law-enforcement agencies encounter.

Roughly three of four controlled-substance cases processed by the DPS lab involve one of the big five drugs that have reliable, long-used field tests — methamphetamine, heroin, cocaine, crack cocaine and marijuana.

Field tests cannot be used in court, but prosecutors use them to strike plea deals, which is how the majority of drug cases are resolved.

The powdery substance gaining all of the headlines and spurring policy changes spurred a better-safe-than-sorry policy that sent all suspected drugs to the lab. And lab protocol was to give substances a complete test — from color testing to confirmation by a GC mass spectrometer, which spits out a document requiring an administrative review.

That process takes time and is resource intensive. So cases started piling up.

There were 2,191 cases in the controlled-substances backlog, according to August data reviewed by The Republic. The backlog consists of cases that have been on hand, pending testing, for more than 30 days — the industry-standard turnaround time.

Controlled substances make up almost exactly half of the DPS lab backlog on all cases, data show. The pileup has dropped substantially from its peak in 2013, largely due to process changes on blood-alcohol analysis and fingerprinting.

But when it came to drug testing, the lab needed another plan.

Now, technicians are using the same types of tests that troopers were using on the streets. As soon as a suspected drug is logged into the lab, it gets a rapid field test.

“That greatly reduces our turn-around time for those cases and increases the number that we can actually do,” Brady said. “… By handling 75 percent of what comes in in this fashion, it’s going to free up the analysts to be able to spend time that’s required on those other cases that don’t fit into this program.”

Officials are optimistic that simplified field tests, which involve dropping liquid into a tray and examining what color things transition to, allay the delays by the end of the year, said Vince Figarelli, superintendent of the Arizona DPS crime laboratory.

The policy itself is slated to stay in place for the time being.

“It may transition,” Figarelli said. “Who knows? We may at some point try to move it back out to the field, but I don’t see that in the near future.”

Why the fentanyl hype, anyway?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention describes fentanyl as “a synthetic, man-made opioid that is 50 times more potent than heroin and 100 times more potent than morphine.”

Often crafted in illicit Chinese laboratories, the drug comes in two forms: one is pharmaceutical and prescribed by doctors to manage pain most often associated with advanced forms of cancer; the other is illicitly manufactured and often gets mixed with heroin, cocaine or other drugs.

Drug users might not be aware that fentanyl has been cut into the other substances, resulting in a more extreme high and contributing to accidental overdoses. It has been among the driving factors behind a series of busts made by law-enforcement agencies across the Valley in recent weeks.

Fentanyl is flowing into the U.S. across the southern border and via the mail system, trafficked by Mexican cartels with vast dealer networks and by small-time operators ordering the drugs online. It’s being purchased by people with opioid addictions looking for the most potent dose on the street and by unsuspecting consumers looking for cheap pain pills from shady internet retailers.

“It truly is everywhere,” said Barbara Carreno, a spokeswoman for the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

And fentanyl is easier and cheaper to produce than heroin, which is derived from poppy plants. With fentanyl, there are no crops, just chemicals.

An August traffic stop led law enforcement to seize 30,000 fentanyl-laced pills, which investigators said were designed to look like oxycodone pills.

Also last month, federal prosecutors said a Phoenix grand jury returned an indictment charging a 45-year-old woman with multiple counts, including distribution of fentanyl resulting in death.

Earlier this year, the DEA confirmed that 32 overdose deaths in Maricopa County between May 2015 and February 2017 were caused by black-market pills laced with illegally made fentanyl that entered Arizona through Mexico.

The concern reached a fever pitch so intense that the DEA in a June report issued an ominous warning about the “significant threat” to law enforcement and other public-safety personnel. The warning stopped short, though, of inciting panic and instead urged the proper use of personal protective equipment when handling the substance.

Federal agents across the state are trained to handle hazardous substances including fentanyl. Agents carry Narcan to counteract any sort of accidental exposure or suspected overdose during routine investigations, said Erica Curry, spokeswoman for the DEA in Arizona.

“The heightened media attention to fentanyl and its analogues is absolutely necessary,” Curry told The Republic, noting, however, that it “should not lessen the scope of the dangers inherent with the use of other illicit drugs.”

USA TODAY contributed to this article.

Follow public-safety reporter Jason Pohl on Twitter: @pohl_jason.