Fentanyl and its derivatives have become the primary driver of overdose deaths in the U.S. These fentanyls caused synthetic opioids to account for one-third of all drug-related deaths in 2016, according to the National Center for Health Statistics. That’s a 700 percent increase from five years ago for manufactured opioids.

December 11, 2017

In 2002, Chechen terrorists took 800 people hostage in Moscow Theater, and Russian special forces devised a peculiar way to subdue them. The tactical team gassed the theater with two types of fentanyl, an opioid known for its extreme strength. One version was 2,000 to 5,000 times as potent as heroin.

The gas killed 125 of the 800 hostages during the siege.

Fast forward 15 years, and fentanyl and its derivatives have become the primary driver of overdose deaths in the U.S. These fentanyls caused synthetic opioids to account for one-third of all drug-related deaths in 2016, according to the National Center for Health Statistics. That’s a 700 percent increase from five years ago for manufactured opioids.

This surge in illicit fentanyl presents a new challenge for families and medical professionals trying to keep loved ones from the harm of opioid misuse. And it’s unclear if the most validated defense for opioid misuse — medication-assisted therapies like naloxone, methadone and buprenorphine — can stem the surge of overdoses caused by fentanyl.

“The jury is still out about how many deaths are going to be saved with fentanyl and carfentanil [through medication-assisted therapy],” said Paul H. Earley, a 30-year veteran in addiction medicine. Wilson Compton, deputy director of the National Institute of Drug Abuse, made similar remarks about “fentanyl specific challenges” to Congress this June:

“There is an urgent need for more research to determine if people using fentanyl or other high potency opioids respond differently to medications for overdose reversal, as well as treatment, and to determine the most effective approaches for utilizing medications and psychosocial supports in this population.”

Still, Earley, NIDA and the other doctors interviewed for this story rely on medication-assisted therapy (also known as opioid substitution therapy) to treat fentanyl addiction, given the technique’s previous history with stymying heroin use and its related overdoses.

Here’s what we know about using this approach with fentanyl.

The MAT blockade

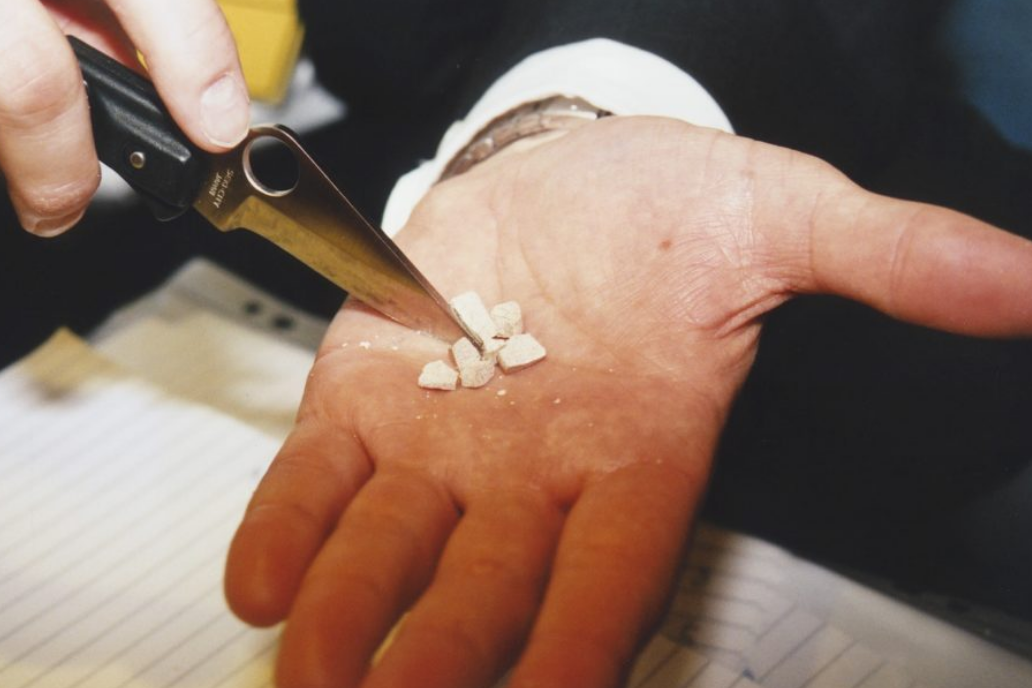

For drug dealers, the allure of illicit fentanyl is simple. Fentanyl and its chemical cousins, like carfentanil, cost about as much as heroin to make ($3,000 to $5,000 a kilo) but can increase profits by millions of dollars. Meanwhile, the drug is as much as 100 times more potent than morphine. Mix a pinch of fentanyl into a bag of heroin, and you’ve got a batch capable of producing 20 times the euphoria and pain relief of heroin alone.

Opioids influence multiple parts of the mind. Some brain areas respond by numbing pain, others produce euphoria. In a fraction of people, these effects lead to addiction. Approximately 80 percent of heroin users start with prescription opioids, according to NIDA, though most of that medication wasn’t originally prescribed for them.

Part of this dependence comes from what happens when the drugs clear the body. The drug’s departure causes an imbalance in brain chemistry — called withdrawal — that can elevate blood pressure, cause diarrhea and trigger feelings of dysphoria and anxiety.

Medication-assisted therapy works by replacing the opioids that trigger the temptation and withdrawal with other, less hazardous opioids. Naloxone, an antagonist often used in overdose emergencies, counteracts heroin’s actions at the nerve receptors responsible for responding to opioids.

Methadone and buprenorphine are long-term treatments that interact with these receptors too, but produce less euphoria and fewer cravings, if taken correctly. Buprenorphine, akin to naloxone, partially works by binding to but not activating opioid receptors.

When people on medication-assisted therapy take heroin, “they basically can’t feel the positive effects,” said Sandra Comer, a clinical neurobiologist at Columbia University and the New York State Psychiatric Institute. “To them it’s almost like getting water. They can’t feel the high that they used to feel.”

This blockade is partially caused by a phenomenon called cross-tolerance. In essence, a person’s brain receptors become so acclimated to methadone or buprenorphine that they resist responding to heroin.

The big unanswered question with fentanyl revolves around whether or not it can override this cross-tolerance blockade. Though doctors have spent the last 50 years using fentanyl for legitimate purposes, such as analgesia during surgery, fentanyl is a relative newcomer to the illicit scene, at least in the quantities being currently trafficked. No one has conducted controlled trials to determine the optimal treatment approaches for fentanyl, according to a review published in February 2017 by doctors at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Comer said that’s still the case.

There are signs that fentanyl is changing the calculus on therapy.

“The main concern is that the relative amount of [fentanyl] opioid in the body may be so extreme that it may take extra doses of naloxone” to treat it, NIDA deputy director Compton told NewsHour.

Compton said his office has seen medical reports that describe doctors needing a continuous IV of naloxone, rather than the typical single injection, in order to reverse an overdose.

Comer’s clinic has observed similar anecdotes with methadone and buprenorphine too. A few years ago, her team started to test for fentanyl the urine of all the people with opioid use disorder who visit her clinic, after hearing rumors of the drug being on the street. Back then, few people who walked through the door tested positive for fentanyl, she said, adding that now the drug is pervasive.

“We’re starting to hear that people are using fentanyl because they can get high even if they’re maintained on something like buprenorphine. Whereas in the past, they couldn’t with heroin,” Comer said.

Earley, who has treated medical professionals with opioid use disorder for decades, has observed the same thing.

“The fentanyl is a siren song, which will pull you back into relapse,” Earley said. “[This relapse] makes sense in terms of my experience with anesthesiologists, who would have fentanyl lying around in the operating room. Even if they were on medication-assisted therapy, they could override it.”

f this trend holds true, it would mirror what scientists have found in animal models of drug addiction, Comer said. Whereas buprenorphine can completely block the response to drugs like morphine or heroin in animals, the therapy only marginally dulls the influence of fentanyl. Though it’s not always the case for drug testing, Comer said, there has been quite a good concordance between the animal data on opioids and subsequent clinical trials in humans.

Earley attributes it to fentanyl’s extreme potency: “The anecdote that you hear about fentanyl decreasing retention in buprenorphine clinics makes perfect sense.”

WATCH: Synthetic opioids are driving an overdose crisis

For Comer, it is an urgent priority to determine whether medication-assisted therapy works to treat fentanyl addiction, both at her clinic and as a recently appointed member of the World Health Organization’s Expert Committee on Drug Dependence.

“I’ve heard some scientists are starting to collect the data on fentanyl, and I keep saying, ‘Please collect this information. Because you really need it,” Comer said.

She specifically wants to study how those on medication-assisted therapy respond to safe and controlled doses of fentanyl, similar to work her lab has done in the past. Earley pitched the idea of collecting urine samples from people currently in treatment, recording who is and isn’t consistently positive for fentanyl and tracking their outcomes. This option would be tricky because fentanyl rapidly passes through the body and the screening is expensive.

“It’s just a big unknown right now, and it’s not only fentanyl,” Comer said. “The scariest thing that’s out there right now is carfentanil.”

“I don’t have something else to offer”

Carfentanil, whose presence is gradually increasing in the heroin supply, is 100 times more potent than fentanyl. It was one of the fentanyl drugs that Russian special forces used against Chechens in 2002, and medical responders didn’t know either the composition of the gas or how to counteract it.

“There was a report of a seizure in Canada [in 2016], where police confiscated a batch of carfentanil that contained enough to kill 50 million people,” Comer said. This batch weighed 1 kilogram, or a mere 2.2 pounds.

The dangerous nature of carfentanil raises another potential worry about medication-assisted therapy with methadone and buprenorphine. If a patient relapses, which happens 10 to 60 percent of the time, then the person may risk a fatal exposure in places where carfentanil or fentanyl taints the heroin supply.

“This is what we believe is contributing to some of the incredible increases in overdose deaths, because carfentanil is an incredibly potent compound,” Comer said. That’s because the drug has a fast onset and produces an incredibly profound decrease in respiration, the main thing that kills people during an opioid overdose. (Fentanyl is so potent that two states want to use it for executions.)

Doctors say medication-assisted therapy saves lives by keeping people from seeking heroin, especially when compared to going cold turkey. Without buprenorphine and methadone maintenance therapy, a person is two to three times more likely to overdose, respectively, making these drugs the sole current option for fighting the fentanyl crisis.

“I don’t have something else to offer. As much as I would love to have absolutely proven techniques to address fentanyl itself, I don’t have this,” Compton said. “What I do have are medications that have been useful for a variety of different opioids, whether people are addicted to prescription opioids or heroin, they [medication-assisted therapies] show a very positive benefit.”

Compton said the major priority right now is finding a way to treat the extreme exposures to fentanyl and carfentanil. The key may be upping the dosage of methadone or buprenorphine, so a user can’t get high off fentanyl, or increasing access to these medication-assisted therapies. But he also floated a fentanyl vaccine as one potential option for the future.

“That’s an approach that some of our [NIDA-backed] researchers are fairly far along in terms of developing,” Compton said. In rodent models, a preliminary version of the vaccine appears able to produce antibodies that clear fentanyl from the brain and prevent an opioid reaction.

But will this vaccine work for all the different variations of fentanyl, like carfentanil? Compton said that’s one of many questions that will need addressing before a vaccine is ready for humans.

READ MORE: How treating opioids with more opioids has divided the recovery community

“Because of the urgency of the overdose situation and the potential for this [vaccine] being very useful in emergency settings, we’re certainly continuing to support it and look forward to their getting to the clinical testing phase,” Compton said.

Earley said that regardless of what emerges therapeutically, medication-assisted therapy will always be a short-run solution — a pitstop on a long road to recovery.

“Because if you’re living in a situation where everyone around you is using heroin or heroin-laced with fentanyl or carfentanil, even if you’re on medication-assisted therapy, it’s just a matter of time before you relapse,” Earley said.

The journey may mean creating a new life: installing barriers to drug use through therapy, getting away from drug-using friends and reconnecting with family.

“There’s no doubt that you have to do more than just put someone on a drug,” Earley said. “You need to teach people recovery skills, drug reversal skills. You need to help people reengineer their lives.”