He said he concluded after the training that “evidence supervision is the scariest job I’ve ever had. When it goes wrong it goes really wrong and you always catch it late.”

May 19, 2018

Editor’s note: The Standard-Examiner is choosing not to name the accused evidence technician because she is a private citizen and as of Friday, May 18, 2018, had not been charged with a crime. An investigation by the Weber County Attorney’s Office continues. It is the Standard-Examiner’s policy to publish names of elected and/or public officials.

Evidence backlogs, insufficient staffing, inadequate supervision and even drug thefts are all too common in police evidence rooms, a national expert who closely monitors the trends says.

“It’s really unfortunate that overall the property room is low on the totem pole and doesn’t seem to get attention until it’s a problem,” said Joe Latta, executive director of the International Association for Property and Evidence.

The Weber County Sheriff’s Office evidence room is undergoing an in-depth audit after the longtime evidence technician was fired Jan. 8. She was found intoxicated on duty the month before and admitted she broke open methamphetamine evidence bags and consumed the drugs for at least a year.In evidence rooms around the country, “Meth and pills have been a real problem the last three or four years,” Latta said.

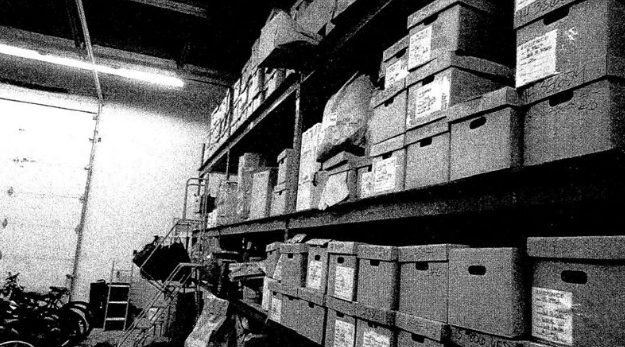

An internal investigation report said Weber’s evidence room was in disarray and dozens of criminal cases may be jeopardized because of stolen or compromised evidence. The Weber County Attorney’s Office is conducting a criminal investigation.

“What you are dealing with is not unusual,” Latta said in a phone interview. “It’s every day. There are many good reasons for it, and when it gets exposed, everybody becomes aware of it.”

Latta, a 30-year veteran of the Burbank, California, police department, teaches evidence management classes nationwide. He’s compiled a running database of about 10,000 incidents, including reports of thefts, mismanagement, and various types of misconduct.

A key benchmark is whether an evidence room is keeping up with incoming evidence while disposing of old items, Latta said.

The Weber County investigation said evidence backlog problems had been growing for at least a few years. Deputies who performed an audit in 2016 told investigators they had to navigate through “deer trails” between piles of evidence.

“If you have 100 deputies who are submitting stuff, you are getting close to needing a second person,” Latta said. “Even if you have a good computer system and everyone is helping, you are drowning in evidence and can’t control it.”

Sheriff’s Lt. Matt Jensen said the agency has 238 sworn deputies in the enforcement and corrections divisions.

“At any given time, one of these deputies may submit evidence into the evidence room,” he said, from cases in the community or those that originate from an investigation inside the jail.

Jensen said 2,379 items were submitted to the evidence room in the final 10 months of 2016 (a new software system was installed in March that year). In 2017, 1,961 items were received, and 1,479 so far this year.

An audit team is going over undetermined thousands of items submitted over the last several years, a process that will take several more months, Jensen said.

“We want to check every package for any tampering or mistakes and restore integrity in our evidence room,” he said.

He said the audit team also is purging several years’ worth of evidence that’s no longer needed.

Kevin McLeod, who was Weber County’s undersheriff until 2014, said he had been concerned about evidence room staffing and now regrets not pushing harder for an increase.

McLeod said the technician “should have never been alone in that evidence room.”

He said adding a second technician was discussed during his tenure.

“As an administrator, it concerned me that we would not, over that kind of assignment,” he said. “They chose to not spend the money to put another person in there, but we should have.”

The internal investigation ordered by Sheriff Terry Thompson blamed Lt. Kevin Burns, who was the evidence technician’s supervisor, for the evidence room crisis.

“I feel someone responsible probably should have pushed harder and made it more of an issue,” McLeod said of the staffing question. “The other aspect of this is that the sheriff is responsible, so you can’t defer responsibility for anything.”

He pointed to Thompson and the chief deputy of the enforcement division, Klint Anderson.

McLeod added: “I hate to see Kevin blamed for what Terry and Klint and the others should have accepted the responsibility for. For Kevin to lose his career over this, I find it unbelievable.”

Thompson decided to fire Burns, but Burns instead negotiated a retirement agreement. Burns remains a candidate for the Republican nomination for sheriff in the June 26 primary election.

In a recent interview, Burns said he attended an evidence room training class in Salt Lake City in 2016.

He said he concluded after the training that “evidence supervision is the scariest job I’ve ever had. When it goes wrong it goes really wrong and you always catch it late.”

Burns said he had lobbied for more help for the technician but was rebuffed.

Latta said supervision is critical.

With many evidence rooms, he said, “there’s not enough supervision, and when there is, they don’t know what to look for.”

An experienced sergeant or lieutenant in a typical department “has been chasing bad guys, going on calls, and knows exactly what to do … but give me that property room, I don’t know what to do with it,” Latta said. “It’s so hard to oversee if you’ve never worked in there.”

And the evidence technician job itself is “very complex,” Latta said, with two or three years needed to develop a full understanding.

Latta said some police agencies have found stability in evidence rooms by using civilian supervisors and evidence custodians rather than sworn officers.

Before Burns was assigned to supervise the evidence room in April 2016, that duty was performed by Steffani Ebert, the sheriff’s office’s chief administrator.

In an email response to questions about her supervision of the evidence technician, Ebert said the employee “did not exhibit behavior that indicated to me she was using drugs, nor did any other employee or source inform me that they believed she was using drugs.”

In the internal investigation, one sheriff’s deputy told investigators she had noticed the technician exhibiting odd behavior consistent with substance abuse as early as 2013, but that observation apparently was not documented at the time.

The report concluded the technician had been stealing drugs from the evidence room for several years.

Ebert said that as of April 2016, when her supervision of the custodian ended, she had been working with her to correct “minor issues” and had assigned one of the custodian’s tasks to another employee so she could focus on her evidence duties.

The employee also was working on an evidence packaging manual to help deputies more often submit accurate evidence information, Ebert said.

“There was no significant problem,” with the custodian at that point, Ebert said.

Latta said most departments don’t drug-test their employees except at the time of hiring — including evidence technicians.

“So they give them all the drugs and there’s no drug testing,” he said.

As for staffing, “it’s a lot easier for a sheriff or a police chief to spend money on things that will make you safe,” Latta said. “But adding a clerk usually doesn’t get a lot of support.

“They’re gonna give them anything they want now,” he said.

You can reach reporter Mark Shenefelt at . Follow him on Twitter at @mshenefelt and like him on Facebook at Facebook.com/SEMarkShenefelt.