Joe Latta, executive director of the International Association for Property and Evidence.

“The older it gets, the more difficult it gets to run it down,

Enter Article DATE HERE

“I want to know who killed my sister, and why did they just leave it go like she was nothing?” Bishop asked during an interview with the Journal Sentinel. “Who is accountable for throwing away her evidence, and why weren’t we ever informed or told?”

No answers from police

When the news organization asked the Police Department those questions, spokeswoman Sgt. Sheronda Grant provided no answers.

“The members of the agency who were responsible for making those decisions in the 1990s have long since retired,” she said in an emailed statement. “However, the Milwaukee Police Department sends its condolences to any family member that was impacted.”

Disposing of evidence in cold cases was once a common practice among law enforcement agencies across the United States. But that had changed before the Milwaukee police cleared out its evidence room in the 1990s, during Philip Arreola‘s tenure as police chief.

DNA was first used in a criminal investigation in Britain in 1986, freeing a wrongly convicted man from prison and identifying the correct perpetrator. The following year, the technology was used in the first U.S. prosecution, helping to convict a Florida man of rape.

After that, authorities learned the value of preserving biological evidence, no matter how many years — or decades — had passed.

Advances in DNA analysis continue. Now, just a few skin cells can yield a full profile. Earlier this year, authorities used familial DNA — the genetic fingerprint of a relative — to charge a man as the Golden State Killer, who terrorized Californians in the 1970s and 80s.

A night at Summerfest ends in tragedy

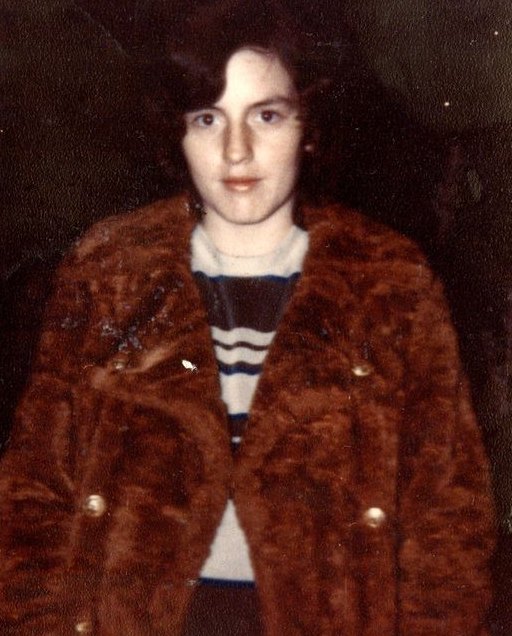

On the last night of Oberg’s life, she and Bishop went to Summerfest with their mother, their mother’s boyfriend and Bishop’s then-husband.

It was a rare night out for Oberg, who was raising an 11-year-old daughter and 9-year-old son on her own. Money was tight, and she was so excited when she got free Summerfest tickets at work, Bishop said.

They listened to country music, ate fried eggplant and drank a few beers.

At the end of the evening, the group headed to a tavern in the 300 block of North Milwaukee Street, where they had parked. Oberg’s mother and her mother’s boyfriend left around midnight, taking the car.

The others decided to stay a while. A guy with a big wad of cash joined their group and kept buying them drinks. He introduced himself as Don, spoke with a southern accent and said he was from Texas.

The man was in his late 20s or early 30s, stood about 5 feet 10 inches tall and weighed about 165 pounds.

He had reddish-brown hair and a thick moustache.

To Bishop, he seemed very nice.

By around 1 a.m., Bishop and her husband had to get back to their baby. They called a cab, but Oberg was chatting with the stranger and didn’t want to leave.

“She said, ‘I’m a big girl now, Val. I can take care of myself. Don’t worry about me,'” Bishop recalled. “We grabbed our stuff and my husband and I left.”

Less than four hours later, a bicyclist found Oberg’s body under the bridge.No list of cases with destroyed evidence

The Milwaukee Police Department doesn’t have a comprehensive list of the cases in which evidence was thrown away. Officials could not say how many cases were affected.

In response to an open records request, police said they were able to locate just one memo from that era touching on what happened. The document lists 50 closed cases in which evidence was discarded. It characterizes the destruction as a “continuing program to reduce the volume of homicide evidence being retained in the homicide storage room at District 5.”

The memo, dated March 4, 1994, describes the evidence as “no longer needed by our department.”

It does not lay out the criteria used to determine which items fit that description.

It also does not describe the scope of the evidence disposal program, which included at least two large purges in the early to mid-1990s, according to several law enforcement sources.

The destruction wasn’t limited to closed cases, according to retired Milwaukee County homicide prosecutors Norman Gahn and Mark Williams.

Gahn, who pioneered the use of DNA evidence in criminal prosecutions in Wisconsin, said he became aware of the missing evidence when he was working on an unsolved homicide case in the early 1990s.

“The explanation I was given was that they needed to make room at the property division,” Gahn said. “I didn’t believe it at first, and then I found out it was true. It was baffling and upsetting.”

Williams said he learned of the disposal around the same time and was given the same explanation by police.

“I was just flabbergasted,” he said.

The district attorney’s office was not consulted before the materials were dumped, according to the two retired prosecutors. Both said they were never given a list of the cases affected or told how many there were.

“They just said it was a lot of cases,” Williams recalled. “We got no notification of it. It was something that always bothered me.”

A murdered 9-year-old. Among those cases, the Journal Sentinel learned, was that of 9-year-old Donna Willing, who was raped and murdered in 1970. The prime suspect in the crime, her neighbor Robert Charles Hill, was never charged because the evidence was destroyed.

If he had been, four children under age 10 might have been spared sexual assaults.

Hill victimized those children in the years after Donna’s death.

Donna Willing was murdered in 1970. (Photo: Journal Sentinel files)

By 2008, Hill was serving a 10-year prison term for the sexual assaults. Around the same time, he admitted killing Donna. Several other confessions followed, but he later said he’d been lying when he made them.

Instead of being prosecuted for murder, Hill was civilly committed in 2012 under a Wisconsin law designed to protect the public from dangerous sex offenders. He remains in a secure treatment facility.

Hill, now 78, is entitled to an evaluation by a mental health professional once a year. If the evaluator ever decides Hill is no longer a threat and a judge agrees, he could be released.

DNA is gone, so crimes can’t be solved

The 1994 Police Department memo makes no mention of DNA or its possible presence among the discarded items.

The Police Department was certainly aware of DNA and its potential to help solve crimes by the time the evidence was trashed, according to Gahn and Williams.

“I knew when they did this that the DNA was just developing at such a rapid pace and in the future there were going to be problems,” Williams said. “I know as I went through my years that there were a number of cases that we had perhaps some new leads on, but we couldn’t verify those because of this.”

Gahn recalled a case that likely could have been solved with that new technology: The 1984 murder of Dorothy Heaggan.

That year, on the evening of Sept. 30,Heaggan’s 15-year-old twin daughters were walking home from visiting a relative when one took a shortcut through the playground of 20th Street School. A man grabbed the girl, ripped off her clothes and stabbed her repeatedly.

Dorothy Heaggan was murdered outside 20th Street School, pictured in 1984. (Photo: Journal Sentinel files)

Heaggan, 34, heard screaming and ran to rescue her daughter. She attacked the man, jumping on his back and smacking him in the head. He threw her off, stabbed her to death and fled. Her daughter survived.

Blood evidence was collected at the scene and analyzed by the State Crime Lab, according to news reports at the time. Within 24 hours, a man who had been harassing young women on the playground over the previous few days was arrested. He was charged in the unrelated sexual assault of a 5-year-old girl, but prosecutors at the time said they couldn’t prove he was involved in Heaggan’s murder.

Four years later, in 1986, a witness told police a different man was responsible for Heaggan’s death. He was arrested but later released when the rudimentary blood testing available at the time ruled him out.

A few years after that, Gahn wanted to take another look at the evidence. But it was gone.

‘If you destroy the evidence, you can never solve it’

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Milwaukee Police Department’s evidence was stored in the basement of the Police Administration Building. The place was a disaster, according to people who worked there at the time.

Evidence was stored in large boxes, which were put into bins with handwritten numbers on them. Nothing was computerized. It was tough to forge a path through the boxes and officers sometimes got tripped up on pipes hanging from the ceiling, according to Thomas Kondrakiewicz, who had been a sergeant at the facility for more than seven years when he retired in 1996.

As the basement overflowed, police moved some of the materials to the District 5 station house on the city’s north side and some to a couple of empty rooms in the downtown branch of the Milwaukee Public Library.

“If something was missing, we searched like you wouldn’t believe,” Kondrakiewicz said in a recent interview. “I would have my people check common numbers, numbers that were close, the next file down. If we couldn’t find it, then we wrote a report on it. Most times, lo and behold, maybe a year later, my person would find it.”

Clearing out evidence in closed cases was sometimes necessary, according to Kondrakiewicz. But he said he never would have signed off on destroying materials that could have been vital to catching killers.

“It was carved in stone, you don’t get rid of that stuff,” Kondrakiewicz said. “If someone was trying to get rid of that stuff, they were crazy.”

Several other Milwaukee officers who worked in the homicide and property divisions during that time concurred.

The 1994 memo said the evidence in the 50 closed cases was “okayed for disposal” by Kenneth Meuler, then a captain in Milwaukee’s criminal investigation bureau, “who personally reviewed” each one.

Meuler told the Journal Sentinel he did not recall doing that review.

He said he never approved throwing away evidence in open homicide cases.

“In a homicide, there’s no statute of limitations and we’ve cleared cases years and years later,” said Meuler, now the police chief in West Bend. “Obviously, if you destroy the evidence, you can never solve it.”

The memo was addressed to Gerald Wawrzonek, who was a lieutenant at the time. Reached last month, he said he only became aware evidence was trashed in unsolved cases after the fact.

“I do recall there was some incident dealing with premature destruction of evidence,” said Wawrzonek, who has since retired. “A copper went through the property bureau to get his evidence and somebody said it’s been destroyed. Who did it, I don’t know.”

The Police Department has not yet responded to an open records request filed in April for reports relating to Oberg’s case. Officials said earlier this month that they were still searching for reports.

Tough to hold anyone accountable

Getting to the bottom of what went wrong all these years later is virtually impossible, said Joe Latta, executive director of the International Association for Property and Evidence.

“The older it gets, the more difficult it gets to run it down,” he said. “It’s not a good thing, but trying to put responsibility on anybody that long ago becomes a fruitless endeavor.”

Latta, a retired California police lieutenant, said he can understand why evidence in closed cases may have been destroyed in the early days of DNA.

But he finds it troubling that the Police Department made the decision to trash specimens in open cases, even back then.

Without the physical evidence, he put the odds of solving Oberg’s murder at virtually zero.

“Unless you have the suspect come forward and say, ‘I’m feeling really bad about it and I’m the one that did it,’ you’re never going to solve it,” he said.

Victims’ families weren’t notified

From the beginning, Oberg’s family has routinely checked in with the Milwaukee police about the status of her case.

About 20 years ago, a detective told Bishop the evidence had been “misplaced.”

“I said let me come down there and see if I can find it,” she said.

But they didn’t let her.

It wasn’t until recently that a cold case detective who answered one of Bishop’s calls told her the evidence was gone — dumped years earlier to make room in the evidence storage facility.

“I was like, ‘What do you mean it’s been thrown away? You don’t just do that!'” Bishop recalled. “They treated her like she wasn’t even a person. Like she didn’t count. And she did.”

The detective told Bishop some of the evidence had been sent to the state crime lab, so there was still hope of catching her sister’s killer.

But the crime lab does not store materials in cold cases, according to Johnny Koremenos, spokesman for the state Department of Justice, which oversees the lab.

“Evidence is returned to the agency that submitted it to the lab, so we would not have any old evidence in our possession,” he said in an email.

State law prohibits him from commenting on specific evidence at the lab, he said.

Also a problem in closed cases

Missing evidence can also pose problems in closed cases, said Rebecca Brown, director of policy at the Innocence Project in New York.

“It’s an incredible miscarriage of justice when this type of evidence is destroyed,” she said. “In many instances, DNA holds the key to freedom for actually innocent people.”

Even when people with valid innocence claims are released from prison, they may suffer lifelong consequences if the evidence is gone.

Some are forced to remain on sex offender registries for life. Others can’t shake the stigma of the accusations against them, Brown said.

Preservation of forensic evidence also can prevent future crimes by making sure dangerous criminals aren’t left free.

Law changed in 2001

In 2001, Wisconsin enacted a law requiring the preservation of biological evidence.

Evidence in closed cases must be retained until everyone convicted in connection with the crime has reached the end of his or her sentence.

To destroy the materials sooner, the law enforcement agency or prosecutor must notify the defense attorney, who then has 90 days to file a motion asking that the evidence be saved or tested.

In open cases, potential sources of DNA should be preserved until the statute of limitations has run out, according to the Wisconsin Association for Identification. That means police must keep evidence in murders indefinitely, since there is no time limit for filing homicide charges.

Several years ago, the Milwaukee Police Department updated its policy, which lists those same time limits for evidence retention, according to Grant.

Many of the elements of the Wisconsin law and its 2005 updates were later recommended by a national committee of experts convened by the U.S. Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology.

But if police in Wisconsin break the law and trash the evidence, there is no penalty.

There is also no recourse for prisoners who can’t prove their innocence because the evidence is gone.

The committee advises state legislatures to put both of those things in place.

Today, Milwaukee police evidence is stored in a warehouse near the intersection of North 27th Street and West Wisconsin Avenue. A computerized barcode system helps officers keep the items organized.

That is little consolation for Bishop.

After Oberg’s death, the slain mother’s children stayed with their father most of the time. Oberg’s daughter lived with Bishop for a while as a teenager.

Both children, now grown, have had their share of problems.

“I would bet money it all stems from losing their mom at such a young age and how they lost her,” Bishop said.

Bishop has gotten past the point of crying for her sister every day. These days, even when she hears one of Oberg’s favorite songs — such as “Why Me Lord” by Kris Kristofferson — Bishop is more likely to say, “Hi, Debbie!” than she is to burst into tears.

She is angry that the Police Department wasn’t straight with her or other victims’ families about the destruction of evidence.

But she has come to terms with the likelihood that her family may never know who killed her sister.

“We may never have the answers we’re looking for,” Bishop said. “It pisses me off, but you just deal with it. You have to.”