Detectives used DNA and genealogy tracing to interview the child’s father, who led detectives to the infant’s mother

April 20, 2019

GREENVILLE, S.C. – A 6-pound newborn girl, wrapped in newspaper and abandoned in a cardboard box in a field on a cold February, left investigators here grasping for answers for nearly three decades.

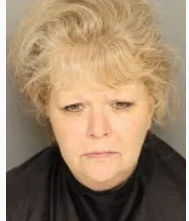

On Thursday, Greenville Police Chief Ken Miller announced a breakthrough in the case of the child known as “Julie Valentine.” Miller said investigators charged the girl’s mother, 53-year-old Brook Graham, in the baby’s death.

The infant was found wrapped in a copy of the Wall Street Journal and floral bedding inside a cardboard Sears vacuum box on Feb. 13, 1990, in a field. A man who was picking Valentine’s Day flowers for his wife found the girl deceased, said retired Capt. Terry Christy, who led the investigation in the 1990s.

Police estimate she was born Feb. 10, 1990, and abandoned immediately after birth. The mother drove the baby to an overgrown area beside a field where a couch and other debris were discarded. The site was within a mile of the mother’s home, Miller said.

An autopsy determined the baby was breathing outside of the womb before she died.

Through the years, the baby has become a symbol for child abuse prevention and the name of the Greenville center that serves child abuse survivors. Police officers at the time raised money to install a plaque in her honor at Woodlawn Memorial Park.

Graham, of Greenville, is charged with homicide by child abuse in the case because investigators determined the child had survived outside the womb, at least for a short time, Miller said. She is being held at the Greenville County jail without bond.

The baby wasn’t born in a hospital, and appeared to have been born in a home, Miller said.

Investigators have said the placenta, sheets, towels and everything that appeared to have been used during the delivery was found inside the box alongside the baby’s body. The baby was full term and did not appear to have any abnormalities, Miller said.

Detectives used DNA and genealogy tracing to interview the child’s father, who led detectives to the infant’s mother, Miller said. The father has not been charged but the investigation is ongoing.

“He has cooperated with our investigation, but people can be deceptive,” Lt. Jason Rampey said.

An arrest warrant states that a review of the vacuum purchase order history showed that Graham and her boyfriend bought the same vacuum tied to the box that held the baby. The couple could not produce the box from the purchase when asked about the vacuum at the time, the warrant states.

DNA testing later linked the boyfriend as being the biological father of the baby and interviews showed there were no other men involved with Graham who could have impregnated her at the time, the warrant states.

“They went to Sears and they pulled the department store’s vacuum order history and that’s what led them to initially reach out to Brook Graham and her then-boyfriend,” said Police Department spokesman Donnie Porter. “They were on their radar from back then. They were able to establish that connection but genealogy was the important missing link.”

Rampey said investigators learned that Graham has other grown children now and the details of those children’s lives were a part of their investigation.

“There was conduct toward the other children that we have questions about,” Rampey said, adding that he had to be vague to protect the integrity of the case.

The infant was named Julie Valentine by detectives because they wanted to give a name to an infant that had no name and had no one to care for her or her interests, Miller, the police chief said.

n 2011, The Julie Valentine Center, a Greenville nonprofit offering free and confidential services to victims of sexual and child abuse, was renamed in honor of the infant.

Honoring a legacy

Shauna Galloway-Williams, the executive director of the Julie Valentine Center, said the child’s life being cut short has been painful to reflect on. She never danced, laughed or went down a slide at a playground, she said.

“This is the complicated nature of child abuse,” she said.

Though an arrest has been made, questions remain. Mainly, why would anybody abandon a newborn child?

“We still have so many unanswered questions,” Galloway-Williams said. “We all ask, ‘Why?’ as if an answer would make us feel any better.”

The decision was made in 2011 to rename the center after the abandoned baby, since law enforcement had already given her a name, “Julie Valentine.” Julianna is the name of Christy’s wife, and Valentine was chosen since the baby was found a day before the holiday.

“We knew it was the right thing to do,” Galloway-Williams said. “The very first day that we re-opened and had clients walk through the door, they told us how much easier it was to walk through the door of a building that said Julie Valentine Center rather than Greenville Rape Crisis and Child Abuse Center. It keeps her name alive. It keeps her legacy alive in the community.”

Galloway-Williams said Thursday’s announcement, while bringing up longstanding grief, also sends a message to others dealing with child abuse cases to always have hope.

She said every time someone reports a case of child abuse is an honor to Julie Valentine’s memory.

“What are we willing to do to ensure there is never another Julie Valentine in our community?” Galloway-Williams said.

‘Always had hope’

Christy has been retired from law enforcement for 10 years but never stopped thinking about Julie Valentine.

He worked for the Greenville Police Department for 32 years before getting a job as a cold case investigator at the Greenville County Sheriff’s Office for five years before retiring.

“It takes more out of you to see a child being violated or neglected like that,” he said. “We always had hope.”

With Graham in custody, other family members can start to heal, but the justice for Julie Valentine comes from the community’s ongoing support, Christy said.

“The justice for Julie is all these years. The love that people have had for her is her justice,” he said.

“Year after year we were hoping someone would finally get a heart and make a phone call to us,” he said. “Then of course the DNA came around and the technology.”