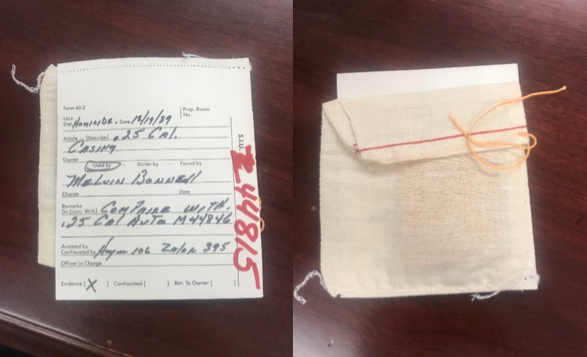

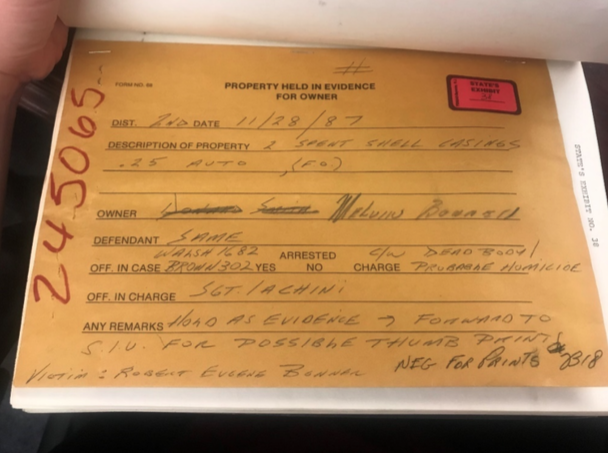

Only a few weeks ago, in February, his defense attorneys found long-lost bullets that were removed from the victim’s body and shell casings that were collected at the scene of the crime, all sitting in envelopes at the Cuyahoga County Prosecutor’s Office

Enter Article DATE HERE

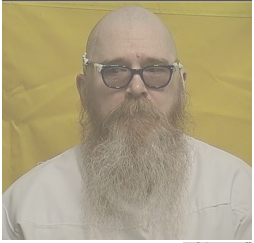

Documents filed this morning with the Ohio Supreme Court argue that newly discovered evidence should allow Death Row inmate Melvin Bonnell to revisit his 1988 murder conviction and course-correct decades of alleged bad faith on the part of the state.

Only a few weeks ago, in February, his defense attorneys found long-lost bullets that were removed from the victim’s body and shell casings that were collected at the scene of the crime, all sitting in envelopes at the Cuyahoga County Prosecutor’s Office. This abrupt discovery came after the office had insisted since the mid-90s that any and all physical evidence tied to this case was gone—except for Bonnell’s corduroy jacket.

The documents—a motion requesting a new trial and related exhibits—paint a confounding picture of how the state has handled this case.

Bonnell was scheduled to be executed Feb. 12, 2020. His death sentence was reprieved by Gov. Mike DeWine, who, unable to secure the pharmaceutical drugs needed to kill state inmates, opted to grant Bonnell another year behind bars. He’s currently scheduled to be executed March 18, 2021. Based on the re-discovery of this physical evidence (and wherever this latest motion leads Bonnell’s case), that extra time on the clock may have made all the difference in the world.

From the jump, Bonnell’s attorneys lay out their argument in today’s filing: “The Cuyahoga County Prosecutor’s Office deceived [the Ohio Supreme Court] and the lower courts.”

Kimberly Rigby and Erika LaHote have represented Bonnell for years, the latest counsel in the Ohio Public Defender’s Office’s decades of work on his case. Since at least 1995, the ongoing argument has been one of access to evidence: Where is everything that the investigators gathered at the crime scene?

As the years went on, DNA testing became an insightful tool in post-conviction relief proceedings. In 2004, Bonnell turned up the urgency on his requests.

Time and time again, assistant prosecuting attorney Christopher Schroeder (who recently left the Cuyahoga County Prosecutor’s Office for a federal post in Alaska) insisted that he’d searched high and low for those pieces of evidence—the bullets, the shell casings, anything. In 2017, Schroeder filed a 124-page report that listed all the ways that he couldn’t come up with a single piece of evidence that Bonnell had been requesting. All told, the entirety of the case was contained in those four boxes at the prosecutor’s office.

“I informed [the defense investigator] that my office had four boxes of material related to the Melvin Bonnell case in our possession, but that those four boxes contained only paper documents,” Schroeder wrote. “I reiterated that my office had no evidence in its possession from Bonnell’s case.”

He went on: “[I] also searched the Prosecutor’s Office file and storage areas for any evidence related to Bonnell’s case. At [my] direction, employees of the Prosecutor’s Office conducted several checks of the inventory of the property room located on the eighth floor of the Prosecutor’s Office. One of those searches also included a physical inspection of the contents of the property room itself for evidence. Each of these searches revealed no evidence related to Bonnell’s case.”

According to court records, investigators had initially tagged the following items in connection with the Bridge Avenue crime scene in 1987: Bonnell’s jacket, his clothing, his car, the murder weapon (a Tanfoglio .25 handgun), two .25 caliber shell casings and a green pillow or cushion from the victim’s apartment. The handgun remains missing to this day, spurring further questions.

In fact, until just a few weeks ago, only the jacket had been recovered—found stashed in a prosecutor’s “closet” after being lost for years. It was tested for DNA evidence in 2008, revealing small specks of the victim’s blood. (In 1987, a serologist tested the jacket and found only Bonnell’s own blood.)

But then, in February 2020, Rigby and LaHote went to the Cuyahoga County Prosecutor’s Office as part of their ongoing requests for discovery. It proved to be a monumental and somewhat awkward turn in the case. While examining the very four boxes that prosecutors had been scouring for decades, the two attorneys found three envelopes containing the bullets recovered from Bunner’s body (“morgue pellets”), two shell casings found at the scene and a third shell casing later provided to investigators by a witness.

“Damningly, [we, Bonnell’s attorneys,] discovered the physical evidence in the Prosecutor’s own file, in the presence of the Prosecutor, within the second of four boxes in the sole possession and control of the Prosecutor’s Office” (emphasis retained from the original).

So, here’s the question at hand: Did prosecutors just totally miss these envelopes the whole time, fumbling the very basic searches that they were ordered to complete? Or had they seen the envelopes, only to turn around and wave off the court, insisting that there was nothing more to get into in this case?

Which is it? The prosecutors’ court-mandated search of the evidence is a duty carried out on behalf of the public to ensure that everything possible is being done in the interest of justice. Bonnell’s two attorneys sifted through the boxes and found these envelopes right away.

So, again, which is it?

Rigby and LaHote also report finding a piece of paper in those boxes that listed witness names as part of a conference with the prosecutor who’d tried the case in 1988. Assistant prosecuting attorney Frank Zeleznikar, who was overseeing Rigby and LaHote’s review of the materials, quickly withdrew the document, saying that it was exempt from records rules and part of the investigative work of his office, according to today’s filing. On the paper, though, the defense attorneys claim to have seen “something to the effect of ‘has never seen b4,'” written next to the witnesses’ names—people who had been at Bunner’s house at the time of the murder.

Another question.

“Melvin Bonnell was weeks from execution in February 2020 while the Prosecutor’s Office was knowingly defrauding [his attorneys], [the Ohio Supreme Court], and the lower courts,” Rigby and LaHote write in today’s filing. “The Prosecutors committed one of the most sinful things that can be done—they lied and deceived to kill and cloaked themselves in the unjustified righteousness of protecting the public. Due to this egregious prosecutorial misconduct, [the Ohio Supreme Court] must now intervene.”

Now, Bonnell is requesting that very court grant a new trial, turning the clock back to 1987 and righting the wrongs committed by the prosecutor’s office in Cuyahoga County.

On Nov. 27, 1987, Bonnell and a friend were drinking their way across the west side of Cleveland. As midnight ticked into Nov. 28, they kept at it. When Bonnell attempted to drive home, police officers signaled for him to pull over. He sped onward and crashed into a funeral home. At the hospital, Bonnell found himself arrested for the murder of 23-year-old Robert Bunner, who’d been drinking with two friends at his place on Bridge Avenue.

A five-day trial in February 1988 ended with two days of jury deliberation. Bonnell was convicted of murder and sentenced to death.

Thomas Chuna, the son of an alternate juror who’d watched the case closely, told defense attorneys that the current frame around Bonnell’s conviction is drastically less stable than what was presented in 1987. “This case haunted my dad since the trial,” Chuna said, according to newly filed court documents. “I can tell you that if my dad was here right now, he would be in tears. He would then explode in emotion knowing that he was right all along in what he thought.”

Defense attorneys like Rigby and LaHote were only recently granted the sort of access they had when they discovered the three shell casings and the two bullets at the prosecutor’s office. Over the past few years in Ohio, the state has opened the doors slowly and extended a progression of access to defendants who are seeking a new trial or some degree of appeal.

In 2016, the Ohio Supreme Court overturned one of its own earlier rulings to allow defendants to examine public records relating to their case. It was a tidal shift for post-conviction relief efforts in the state, one that ensured state and local law enforcement agencies, like county prosecutor’s offices, could no longer withhold records from defendants (the case is called State ex rel. Caster v. City of Columbus et al.). In the past, public records relating to defendants’ cases were exempted from formal requests, for “specific investigatory work product” reasons.

Then, in 2017, the state enacted Rule 42, which applies to the post-conviction review of capital cases in Ohio. “In a capital case and post-conviction review of a capital case, the prosecuting attorney and the defense attorney shall, upon request, be given full and complete access to all documents, statements, writings, photographs, recordings, evidence, reports, or any other file material in possession of the state related to the case,” according to Ohio Court Rules.

The latest discovery in Bonnell’s case echoes events that followed the 1989 wrongful conviction of Joe D’Ambrosio. In that case, D’Ambrosio was convicted of a murder that happened on the east side of Cleveland. It took a federal judge to order the Cuyahoga County Prosecutor’s Office in 2002 to turn over exculpatory documents related to D’Ambrosio’s case—documents that contained information pointing directly to the alternate suspect in the murder and revealing the police department’s own uncertainties about the investigation into D’Ambrosio.

In 2009, D’Ambrosio’s murder convicted was vacated—after years of tenacious wrangling on the part of the Cuyahoga County Prosecutor’s Office. He was formally exonerated in 2012.

As of today, D’Ambrosio is one of the 2,577 men and women who’ve been exonerated the U.S. since 1989. In most of those cases, if not as a general rule, the process is grueling and time-intensive, playing out over many years before a defendant’s dubious conviction gets another close look by the criminal justice system.

As recently as March 4, 2020—after the defense attorneys’ discovery of the bullets and casings, and before this latest motion was filed—the prosecutor’s office filed a response to Bonnell’s request for the Ohio Supreme Court to take up his case.

“It cannot be disputed that Bonnell has been aware since at least 1995 that the items in question were not preserved for testing,” assistant prosecuting attorney Frank Zeleznikar wrote (shortly after Schroeder had left the office). “The extensive record documenting Bonnell’s knowledge of that fact is recounted at length … . He’s known this evidence was lost or destroyed because the State continuously, at every point in the last 24 years, has acknowledged that the evidence was not preserved. This has never been a secret. The State never hid it from Bonnell. For Bonnell to now claim that this information is new to him ignores the last 24 years of litigation, all [of] which is preserved in writing on the court’s docket.”

The thinking here is that DNA testing of the bullets and shell casings may offer a definitive understanding of who touched them—who loaded the gun, who killed Robert Bunner on a November night in 1987. For any open questions in this case, and there are many, the DNA testing of this newly discovered evidence offers one way forward.

“Deceiving the courts and Bonnell for years while simultaneously seeking to execute him is egregious and the highest form of prosecutorial misconduct,” his attorneys write (emphasis retained).

Cases like D’Ambrosio’s and Bonnell’s are variations on a theme. The criminal justice system has been slow to acknowledge the problems caused by stubborn prosecutors who are unwilling to revisit questionable cases. When exculpatory evidence is withheld, historically, there have been few avenues for defendants to investigate their own case further. With the Caster decision and Rule 42, Ohio is moving in a direction that grants the obvious: mistakes are made, humans are fallible, the system is imperfect. It’s never too late to deliver justice in this world.

Until it is too late. As of this writing, Bonnell has 353 days to live.