“Investigators collected several pieces of evidence in 1979, including the killer’s DNA from semen found inside Day’s body”.

March 29, 2021

GREELEY, Colo. — A Kansas man with a lengthy rap sheet has been charged with murder in the 41-year-old slaying of a Colorado college worker found sexually assaulted and strangled in her car.

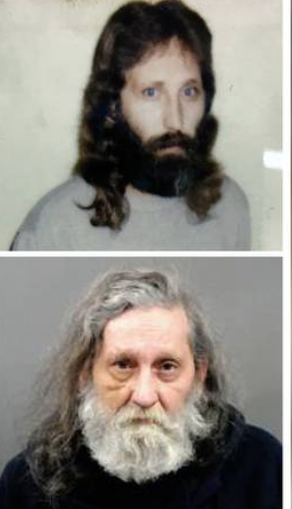

James Herman Dye, 64, of Wichita, is charged with two counts of first-degree murder in the Nov. 26, 1979, death of Evelyn Kay Day. He was arrested March 22 and booked into the Sedgwick County Jail, where he remained Monday awaiting extradition to Colorado.

Weld County District Attorney Michael Rourke explained at a news conference Friday that the two counts of murder represent differing theories of Day’s killing. The first, murder after deliberation, alleges that he committed the crime with the intent to kill Day.

The second, felony murder, alleges that he caused Day’s death in the commission of another felony, in this case, a sexual assault.

Prior to Dye’s arrest, Day’s killing was the second-oldest unsolved cold case homicide in Weld County. The oldest, according to Weld County records, is the June 23, 1975 disappearance and slaying of Margorie Sue “Margie” Fithian, who was last seen alive with her 18-month-old son at a Denver bus station.

Fithian, 23, of Greeley, was shot twice in the face on the side of a dirt road a few miles north of Roggen, about 60 miles from Denver in rural Weld County. She died en route to a hospital.

“Her son, who was unharmed, was found on the side of the road with his mother, holding her hand,” according to the Weld County Sheriff’s Office website.

Like Day, Fithian worked at Aims Community College in Greeley.

A disappearance in the nightDay, 29, of Evans, was last seen alive around 10 p.m. the night of the crime as she locked up the business lab at Aims. Day, who went by her middle name, worked there as a lab monitor.

She made it at least as far as her car, according to a student who left at the same time. “(Student) Julie (Cogburn) said as she left the campus, she saw Kay in her car in the parking lot,” an affidavit in the case states.

The next morning, Day’s husband, Stanley Charles “Chuck” Day, awoke to find that his wife had never come home from work. He reported her missing with Evans police officials and informed Patricia Harder, one of his wife’s colleagues, that she had vanished. He gave Harder a description of Kay Day’s red 1977 Datsun station wagon.

Around 5:30 p.m. that evening, Harder and a colleague, Warren Ptacek, were driving home when they spotted the Datsun parked along the eastbound shoulder of West 20th Street, under a water tower just off the Aims campus.

“Patricia told Warren that the car appeared to be Kay’s, and that she was missing,” the affidavit states.

The pair parked behind Day’s vehicle and Ptacek got out and peered inside the station wagon. He found Day’s lifeless body in the back area of the car.

Harder ran to a nearby fitness center and called 911.

“Kay had been beaten, sexually assaulted and strangled to death with the cloth belt of her own overcoat,” Weld County Sheriff Steve Reams said Friday.

Day’s cousin, Jennifer Kerr, told CBS Denver that she could not understand why anyone would kill her cousin, who she described as a sweet woman. Day and her husband had two sons, one just 6 months old when she died.

“Why? Why? Why would you take the life of someone so vibrant?” Kerr said. “I can’t comprehend it.”Investigators collected several pieces of evidence in 1979, including the killer’s DNA from semen found inside Day’s body.

It would be decades before the use of DNA evidence to solve crimes became commonplace. The Colorado Bureau of Investigation was able to determine from the vaginal swabs, however, that Chuck Day was not the man who’d attacked his wife, according to court documents.

Several leads failed to pan out and the case went cold.Fresh eyes on the case

Last May, Weld County Sheriff’s Office officials appointed Detective Byron Kastilahn to a newly-established position as a dedicated cold case investigator, Reams said in a statement. As one of his first tasks, Kastilahn identified 10 cold cases to prioritize for immediate investigation.

One of those was the Day case. Kastilahn asked the Colorado Bureau of Investigation to run the DNA profile of Day’s alleged killer through the FBI’s combined DNA Index System, or CODIS.

On Aug. 26, the database produced a match: convicted felon Dye.

Dye, who lived in Evans at the same time as Day and her family, had a criminal history in both Colorado and Kansas, authorities said. In October 1977, two years before Day was killed, he was arrested in Weld County and charged with sexual assault.

He was charged with the sexual assault of a child in February 1981 and with attempted sexual assault in May of that same year. Records of any prison time he served were not immediately available.

CBI officials found that Dye’s DNA profile matched that of the semen found inside Day during her autopsy, according to the affidavit. His profile also linked him to genetic material found on the sleeve of Day’s coat, as well as fingernail scrapings taken from Day’s right hand.

“During the following months, Kastilahn dedicated his time to reviewing old case notes and re-interviewing family members and other persons of interest in the case,” the sheriff said in his statement.

That review included 40-year-old records from Aims Community College.

“(Kastilahn) learned Dye, who would have been in his early 20s at the time, was a student enrolled in automotive classes in the summer and fall of 1979, the winter of 1980 and the summer of 1982,” Reams said.

The detective sorted through case documents to determine if Dye’s name had ever come up in connection with the investigation. He found a 1988 tip submitted to Weld County Crime Stoppers in which the tipster said he had information on a killing at Aims Community College nine years before.

The caller named James Dye as the suspect.

“RP advised it has been a few years since he has heard from subject, but gave the following info: Subject used to work on a farm east of Platteville; unknown if still there,” the narrative of the tip stated. “RP stated that subject is either the one who killed the girl or is very much involved in the murder.”

The tipster told Crime Stoppers that on the night of the crime, Dye came home with his clothes soaked with blood, the affidavit states. He destroyed the clothes soon after returning home.

“He then sat down to watch the news on TV,” the narrative said. “He … told his wife (now ex-wife) that there was a girl killed out at Aims.”

Dye told his wife about Day’s murder before it was on the news, the caller said.

The caller added that Dye’s ex-wife would be able to explain more about what happened, but he became “slightly uncooperative” when asked for the ex-wife’s name or Dye’s current whereabouts.

Kastilahn found no evidence that investigators ever followed up on that 1988 tip.

The cold case detective went back to Aims for more records, including Dye’s official transcript and his class schedule for each of the terms he was a student. The records showed that Dye was taking a steering and suspension system course in the fall of 1979, when Day was slain.

That course was taught in the campus’ Trades and Industry Building.

“A map in the Aims catalog showing where the college buildings were in 1979 showed that the Trades and Industry Building was directly north of the Business Building where Kay was working,” the affidavit states.

Dye’s transcript showed that his academic pursuits began to falter around the time of Day’s homicide. He failed to complete the four classes in which he was enrolled during the winter 1980 semester.

He also received no credit for his sole class in the summer of 1982.

“These records showing defendant’s attendance and performance at Aims in the following days, weeks and quarter after Kay’s murder are relevant in showing a change in his behavior after said crime,” a detective wrote.

Kastilahn tracked down Dye’s ex-wife, to whom he was married from 1977 to 1981. Both she and one of Dye’s sisters told the detective they believed he was capable of murder, according to court records.

Another sister said their mother, Viola Kubacki Dye, had admitted to her that she believed James Dye had killed Day. Viola Dye has since died.

The cold case detective also looked at the other crimes Dye had been accused of committing in the past. In his Oct. 4, 1977, sexual assault case from Weld County, the victim told police she was driving home from Loveland when she spotted a man standing near a car on the side of the road.

A woman was also there, holding a baby, so the victim, who had her children with her, said she felt it was safe to stop and offer them help, the affidavit states.

The man, later identified as Dye, asked the victim for a ride to his house. She agreed and began driving to the address he gave her.

“She said they ended up on a remote dirt road, and all of a sudden, (Dye) grabbed (her) by the neck and throat with both hands,” the police report stated. “He put the Impala in park and told (the victim) to get out of the car.”

Dye forced the woman to walk to an area with trees and bushes nearby and raped her, according to authorities. He then had her put her clothes back on.

The victim ultimately called the police and Dye was arrested. It was unclear if he was convicted of the crime.

The affidavit states that the crime shows a similar modus operandi, or mode of operation, to that employed in the Day homicide. Day was strangled, and detectives believe Dye may have asked her for a ride.

Day was also fully clothed when her body was found, despite being sexually assaulted, the affidavit states. Investigators believe Dye may have made her redress herself before he killed her.

Kastilahn and another detective tracked Dye down at his home in Wichita, where they questioned him about the Day case. During the interview, he denied knowing the slain woman or having a sexual relationship with her.

Dye denied ever touching Day and said he had never heard of her slaying or followed the case, despite her employment at his school. Once the detectives had his denials on the record, they obtained a warrant for his arrest.

When asked why it took so long for investigators to link Dye to Day’s death through the DNA on file, Kastilahn pointed to the sheer number of cold cases on the department’s books. As of Monday, a total of 21 cold cases were listed on the agency’s website as remaining unsolved.

Kastilahn said Friday that the true number is more than 40 cold cases for which he is now responsible. He said Reams helped out by narrowing down the priority cases, which include the oldest cases in the files.

>> Read more true crime stories

The detective requested that the DNA evidence in the Day homicide be run through CODIS weeks into his appointment as cold case detective.

“The detectives in 1979, the field evidence technicians, did a great job by gathering the evidence,” he said. “Without that, we probably wouldn’t have a case.”

The technicians preserved the evidence despite the fact that DNA technology was decades away.

“They had the foresight to be thorough in their evidence processing of the crime scene,” Kastilahn said. “That was fortuitous for us.”

Kerr, Day’s cousin, told the CBS affiliate the family had feared the case would never be solved. The phone call saying an arrest had been made came as a complete shock.

“This just came out of nowhere,” said Kerr, who represented Day’s family at the news conference last week. “It feels like a victory.”

Kerr was thankful that the news came while her aunt, also named Evelyn Kay, was still around to hear it. Kay Day’s mother turned 100 last week.

“Thank you so much for not giving up on this case,” Kerr said in a message for investigators. “It means so much to our family.”