June 11, 2021

A year ago, Susan Pater and Alice Juan were packing up their parents’ home in Southeast Portland when they stumbled upon photos of their beloved sister, Barbara.

Forty years had passed since Barbara Tucker was murdered at Mt. Hood Community College.

In the family photos, Barbara never ages past 19. She was almost 6 feet tall, strong and athletic. Her hair was light brown, her eyes a warm, chocolate brown. She was outgoing, smart and determined. A “goofball,” a family friend said.

“We talked about the case that day, and we both felt it was never going to be solved,” said Juan, 65. “We had both accepted it.”

But on Thursday, the sisters are testifying before a Multnomah County grand jury after a breakthrough in the case. Using advances in DNA, Gresham police identified and arrested Robert Plympton, 57, as a suspect in Barbara Mae Tucker’s 1980 murder. Plympton pleaded not guilty at his arraignment Wednesday.

Plympton’s arrest this week brought overwhelming emotions for the family. While the extraordinary break in the case provides some comfort for Barbara’s sisters, it also has re-ignited their grief.

“Someone brutally took her away from us when she was so young, and went on living their life after,” said Pater, 63. “We want to see some justice, and we hope this is the right person.”

Plympton, a longtime Troutdale resident who is married and has a son, remains in custody at the Multnomah County Detention Center. At the time of Tucker’s murder, Plympton was 16 and in high school.

Investigators were led to Plympton through the work of Cece Moore, a Virginia-based genetic genealogist who runs a group called DNA Detectives.

In the Tucker case, DNA collected from the crime scene was entered into the GedMatch database, and a match emerged. Plympton was identified as sharing less than 1% of DNA with the match — likely a distant relative.

In Moore’s process, she finds common ancestors and pieces together the unknown suspect’s family tree until it converges and points to one person or a handful of people, usually narrowed down by a geographic region to the crime or other factors like age or hair or eye color. That ultimately pointed more directly to Plympton, and police began investigating.

In an interview with The Oregonian/Oregonian Thursday, Moore called the breakthrough “a highlight of her career.”

“I’ve worked on hundreds of cases, but this case stuck with me unlike any others,” Moore said. “I would wake up thinking about it and go to sleep thinking about it. I’m so happy the family will get some answers, though I don’t believe there’s ever closure. But if he’s convicted, there may be some justice.”

Susan Pater keeps a picture of her sister Barbara Mae Tucker in her Portland home. Mark Graves/The Oregonian

‘It’s still so hard’

On Thursday, Plympton’s criminal history began to come into sharper focus. Oregon Department of Corrections records show Plympton was convicted of second-degree kidnapping in 1985 in Multnomah County and served a 30-month sentence that ended in December 1987.

He served two other six-month stints in prison between 1993 and 1997 for driving under the influence of intoxicants convictions and parole violations.

He was accused in 1997 in Multnomah County of attempted sodomy and assault in an attack on a woman, but the case was dismissed after a grand jury found insufficient evidence to file a criminal complaint.

Earlier this week, Gresham police detectives knocked on the door to Pater’s Southwest Portland home.

They’d solved Barbara’s murder, they told a stunned Pater. She’d assumed her sister’s killer was long dead.

A hallway in Pater’s home is lined with family photos. She thought recently that it may be time to declutter, to finally take down the pictures of ‘Barby’ and the siblings from their childhood. Barbara was the youngest of seven in a blended family.

“But I’m glad I still have that in the hallway,” Pater said, her voice breaking. “It’s still so hard. I’m upset that it wasn’t solved sooner.”

Their mother, Louise Tucker, died in 1995, and their father, Albert Tucker, died in 1989. Barbara’s death left them heartbroken, she said. It was the first time they saw their father cry.

“All this time went by, and my folks never got to see it solved,” she said.

Norm Frink, a now-retired chief deputy for the Multnomah County District Attorney’s Officie, recalled staying in touch with the family as his office worked the case in the 1980s.

Louise Tucker wrote him letters frequently.

“She was shattered by the death of her daughter and wanted more than anything to see her killer brought to justice,” Frink said.

He remembers pouring over reports and records in the “extremely frustrating” case that remained unsolved, despite several witnesses who saw Barbara that night.

“I only wish this had happened sooner, but the tech has evolved and fortunately there’s finally been an arrest,” Frink told The Oregonian/OregonLive. “It’s a positive development, and I’m just sorry Mrs. Tucker didn’t live to see it.”

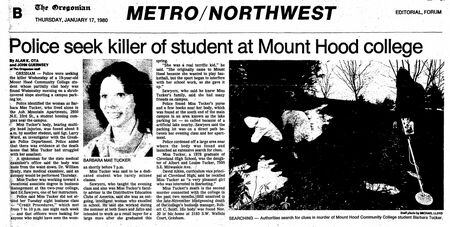

An archived Oregonian article about the murder of Barbara Mae Tucker in January 1980 reported that Tucker’s partially clad body was found in a shrub-covered slope at Mount Hood Community College.

‘Never forgave herself’

Barbara Tucker was a sophomore studying business at Mt. Hood Community College when she left for a night class on Jan. 15, 1980.

Multiple witnesses who drove by saw Barbara running onto Northeast Kane Drive from the wooded area on the west edge of campus. They recalled thinking she was waving at someone and trying to get people’s attention. But no one stopped to help her.

A witness saw a man emerge from the shrubs and lead her back toward campus. A student found Tucker’s lifeless body in some nearby bushes the next morning. The medical examiner determined Tucker had been sexually assaulted and beaten to death.

Her purse and books were found nearby. The family believed she may have accepted a ride from someone, because she wouldn’t have walked to class that cold, rainy night.

“Our poor mother never forgave herself for letting Barby move out to Gresham for college,” said Juan, who now lives in Independence.

Louise Tucker never gave up hope, though, Juan said.

‘Bad things happen to good people’

Maria Adrian, Barbara’s childhood best friend, doesn’t feel like she can get excited about Plympton’s arrest.

“I’m going to wait patiently until the grand jury comes back to say whether there is enough evidence to prosecute,” said Adrian, 59, of Portland. “He could walk free. Maybe he could get jail time. We don’t know.”

Barbara’s murder had a long-lasting effect on Adrian. She anxiously waited for her own children to pass the milestones Barbara never got to achieve. After her children graduated from college, got married and settled into their lives, she could finally breathe, she said.

“Bad things happen to good people, and there’s nothing I could do to change it,” Adrian said. “There were no clues that this would happen to Barbara. I came to terms with it a long time ago. I know she went through hell those last couple hours as she was dying. After that, I watched her family go through the pain, but I knew she wasn’t hurting anymore.”

‘She loved to goof around’

Barbara played basketball at Cleveland High School. She went to a national competition and won awards while involved with Distributive Education Clubs of America, a club for students interested in business and retail. In the summertime, she worked at Sears.

Barbara sewed, knitted, crocheted and loved arts and crafts, Juan said.

“She’d come home from school and say, ‘I’m going to go knit myself a top’ and then come upstairs an hour later with clothes she made from scratch,” Juan said.

Barbara was ambitious, Pater said. She was the first in their family to go to college.

“I wish we could’ve seen what she would’ve done with her life, I know it would’ve been amazing,” Pater said.

Barbara loved writing songs and playing her guitar. She wrote poems. She dreamed of opening her own craft supply shop one day after she got a business degree.

Adrian remembers a summer day when she and Barbara were riding around in a friend’s convertible, with the top down in “the middle of nowhere” Gresham, blasting pop music and singing loudly to the radio.

“We got pulled over by the cops because we were sitting in the backseat with our feet on top of the backseat, and dancing,” Adrian recalled. “Barby turned around and really seriously said, ‘You guys, buckle up quick, we’re gonna get in trouble, put your seat belt on.’ And we were cracking up laughing. She loved to goof around and have fun, but she was serious about not getting in trouble.”

‘She will always be 19’

Juan, who is now in her 60s, is still grappling with the realization that Barby will never age.

“The saddest part is that she will always be 19,” Juan said. “We didn’t get to watch her grow up, we didn’t get to see her turn into a woman, who could’ve had her own business, get married and have children of her own.”

About a decade after Barbara’s death, Juan was upstairs in the family home in Southeast Portland, painting a hallway and cleaning in Barbara’s old bedroom.

Louise, their mother, said, “Pack up Barby’s stuff.”

“It was so strange because my mom was finally letting go, which meant I had to let go.”

The family was raised in that house, which their father bought in 1941 in the Westmoreland neighborhood.

After Barbara died, their mother bought a single yellow rose and planted it in the garden.

Like Barby, the rose bush grew strong and tall, Juan said, and every spring Barby’s roses bloom.

–Savannah Eadens; seadens@oregonian.com; 503-221-1651; @savannaheadens

Note to readers: if you purchase something through one of our affiliate links we may earn a commission.